By Gregoire Canlorbe

Warning: This article lies on a metapolitical and ideal level, and not on a programmatic and political level.

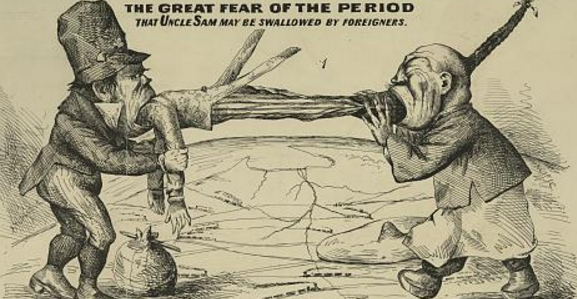

The obsession of liberals (libertarians, either “classical liberals” or “anarcho-capitalists”) with condemning economic or Cultural Marxism is a dead end. Saving Western civilization requires the wisdom to identify, and the courage to name, the true contemporary enemy of the West: cosmopolitanism. Cultural Marxism is a sluggish expression, which may at best designate Gramsci’s doctrine that Marxists must, before attempting the Revolution, achieve cultural hegemony; as for economic Marxism, which is only a way of designating Communism and planning, it subsists at the margins. Cosmopolitanism is the ideology promoted by the “global superclass,” according to the expression popularized (if not initiated) by Samuel Huntington: the world superclass consists of a transnational network of uprooted and denationalized people, whose gestation dates back at least to the beginning of the twentieth century and whose constitution accelerated with the fall of the Soviet bloc. This article aims to elucidate the conceptual relations between liberalism (libertarianism) and cosmopolitanism, and will outline the contours of a new variety of liberalism: a liberalism simultaneously directed against bourgeois nationalism and against cosmopolitanism.

Definition of cosmopolitism

By cosmopolitan ideology, one must understand the ideology that rejects humanity divided into nations. As such, cosmopolitanism condemns the particular mode of organization that characterizes a nation, which confers on a group of individuals the identity and unity of a nation. That mode of organization is the following: a relative genetic homogeneity, as well as cultural; a chain of social and juridical ranks that goes back to a sovereign political authority (i.e., the supreme authority within the government); and a territory that is covered by, and which limits, this hierarchical and homogeneous organization. Cosmopolitanism attacks the sense of territory, and therefore borders, by forbidding governments to defend nations against indiscriminate free trade or free immigration. It also attacks the juridico-political hierarchy of a nation in advocating the sole income and occupation inequalities, or in defending a world government. Finally, cosmopolitanism condemns the genetic and cultural differences between nations: not content with advocating the relativism of values within each nation – i.e., the abolition of moral boundaries enacted within them – it praises the leveling of races and cultures.

It is a mistake to believe that the cosmopolitan elite cultivates the ideal of a humanity reduced to its animality. The ideology of the world superclass abhors, very precisely, these fundamental instincts of human nature that are territorialism the will to domination, identity and adventure, which are so many distinct expressions of the aggressiveness coded in our genome. The ideal that cosmopolitanism cultivates is actually that of a humanity in which the instincts of territory and identity, and thus the attachment to frontiers, are no longer expressed; and of a humanity in which the instincts of adventure and domination, and thus the taste for competition and war, are no longer expressed. A humanity deprived of its national and cultural rooting – but also, more fundamentally, of its biological rooting – is the horizon of cosmopolitan ideology. In the field of values and moral boundaries, let us point out that the cosmopolitanism of the world superclass diverges from the pur et durcosmopolitanism, in that the ideology of the world superclass counterbalances the call to ignore moral boundaries (on behalf of individual emancipation) with the concern for preserving and establishing typically bourgeois values.

Although the concept of “cosmopolitanism” was brandished for the first time by the Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope, it is far from being evident that Diogenes (and in his wake, the Stoic philosophers) understood cosmopolitanism in its current sense of an ideology preaching the relativism of values and the leveling of races and nations. It may well be that cosmopolitanism in its Classical sense was only the philosophy that everyone belongs – on a moral and bio-cultural level – to a given nation, and in a “spiritual” sense belongs to all of humanity as well: such a conception does not mean the rejection of nations. Be that as it may, what will concern us here will be cosmopolitanism as it is understood (and set up) by the world superclass; and it will be liberalism envisaged in its relation to the cosmopolitanism of the world superclass: a cosmopolitanism that advocates bio-cultural leveling and a certain moral relativism, but which remains attached to these properly bourgeois values that are the hegemony of economy, contempt for virility, the materialist approach to reality, and puritanical or feminist moralism.

The three faces of the equalitarian utopia

For the overwhelming majority of liberals, they (be they academics or simply followers of the liberal philosophy) refrain from denouncing cosmopolitanism and envision Marxism as the only enemy to fight. What is more, they indulge in cosmopolitanism at various levels, whether or not they use the term cosmopolitanism; and whether that ideological stance is conscious on their part or is so natural that it goes unnoticed in their own eyes. Is that situation the sign that liberalism is culminating as cosmopolitanism: in other words, that cosmopolitanism constitutes the logical outcome of liberalism; and that the endorsement of cosmopolitanism among liberals is, therefore, neither accidental nor contingent (but responds to a conceptual necessity)?

Before we answer, it is not useless to highlight the kinship of liberalism, socialism, and cosmopolitanism. Those three ideologies (or philosophies) are ultimately the three distinct manifestations of the same egalitarian ideal. Indeed, liberals, socialists, and cosmopolitans are enemy brothers, animated by a common passion for equality; even though it is a faith, an ideal, that they embody in three distinct ways: universality of law for liberals, equality of income for socialists, and the leveling of races and nations for cosmopolitans. Let us add that liberalism, socialism, and cosmopolitanism – as they have unfolded since the French Revolution – also converge in their common adherence to the hegemony of economy in the scale of values. Such hegemony is not a wishful vow on the part of egalitarian ideals: as rank inequalities were dissipating (in accordance with the liberal ideal of equality in law), economics has gradually lifted itself (since the Revolution of 1789) to the summit of Western values. By the same token, the welfare state has gained ground (in accordance with the socialist ideal of economic equality), and cosmopolitanism itself has finally contaminated the intra-national mores and relations between nations.

Let us be clear about what makes the singularity of each of the three heads of the equalitarian hydra. The universality of law – or the equality of human beings with regard to the rules of law that must apply to them – serves as the fundamental value of liberalism. The essential propositions of that philosophy always boil down to some justification or affirmation of the value of equality, understood in its legal sense as equal freedom for all equal escape from all coercion (in their lives and in terms of the goods they can acquire). For socialism, it is equality in an economic sense – income equality and central planning – which serves as a fundamental value; and for cosmopolitanism, it is equality taken in a biological, cultural, and “communitarian” sense: the equality of men in the sense of their biological and cultural lack of differentiation, and in the sense of their not belonging to any other collective than humanity. That everyone should be culturally and racially identical, that no one should be a member of a nation within humanity, that everyone should be a member of humanity considered as a collective in its own right (and that one should be a member of that collective only), that the individual should be released from the values and moral boundaries that his affiliation to one or another nation assigns to him, and that he should everything which “thwarts” and separates individuals should be removed: this is the egalitarian creed of cosmopolitanism.

From classical liberalism to anarcho-capitalist cosmopolitanism

In its chemically pure form, so to speak, liberalism merges with an anarchism that respects private property – and, in particular, the private ownership of the means of production. Knowing whether the “truth” of a doctrine lies in the extremist, radical branch of that doctrine or in its moderate, “pragmatic” branch is an insoluble problem: it is a matter of arbitrary consideration, of “subjective preference,” rather than a means to identify the authentic meaning of a doctrine with what its radical or moderate branches affirm. Therefore, it would be futile that we ask whether anarcho-capitalist liberalism is “truer” or more “authentic” than so-called classical liberalism. But it is not vain to determine whether integral liberalism, in addition of being anarchist, is also a cosmopolitanism (out of logical and conceptual necessity). We will see that anarcho-capitalism only serves to exacerbate the cosmopolitanism already present in classical liberalism.

The classical liberalism of John Locke, Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, the Mill father and son, Robert Torrens, Frederic Bastiat, Yves Guyot, Ludwig von Mises, or Friedrich August von Hayek, not only affirm its attachment to equality in law, or universality in the rules of law, but promotes an extended division of labor, and praises the entrepreneur as the one who coordinates the division of labor (on the basis of his anticipation of the fluctuations in demand), spurring the allocation of factors in anticipation and in the direction of long-term equilibrium (where capital is allocated in such a way that entrepreneurial decisions have correctly anticipated the priorities now displayed by the demand for consumption or investment). Anarcho-capitalism lies in the vein of classical liberalism, except that it rejects the “minimal state” promoted by classical liberals; and calls for privatizing (and opening up to competition) the regal functions, to put an end to the state’s legal monopoly on the use of force to sanction the rule of law.

The greatness of classical liberalism (that culminates in anarcho-capitalism) lies in its double demonstration of the superior productivity of the extended division of labor, and of the need for the free market – and a fortiori the free market for capital goods, in the absence of which there can be no anticipation and no calculation of the profitability of allocation decisions – to coordinate the division of labor in the direction and in anticipation of the optimal satisfaction of the demands for consumption and investment. The mediocrity of classical liberalism lies in its contempt for the warlike spirit, and in its pacifist ideal, which degrades human nature, given that it is the case – as Hegel knew so well – that “the movement of the winds preserves the waters of the lakes from the danger of putrefaction, which would plunge them into a lasting calm, as would do for the peoples a lasting peace and a fortiori a perpetual peace.” Let us note that the pacifism of classical liberalism has remained wishful thinking to this day; and that the West after the Revolution of 1789 did not see the end of war, but only of the warrior spirit: we will return to this subject later.

Anarcho-capitalists, as much as classical liberals, by the very necessity of their doctrine indulge in cosmopolitanism. While classical liberalism merges with a relative cosmopolitanism, anarcho-capitalism merges with a more pronounced cosmopolitanism. While classical liberalism affirms the existence of nations, and nonetheless promotes the indiscriminate opening of borders to goods and migrants (in the name of the ideal of a division of labor whose scope transcends political boundaries), anarcho-capitalism denies or condemns the existence of nations themselves. The reason for that animosity lies in the fact that anarcho-capitalism draws all the implications of equality in law, which is tantamount to saying that it aspires to an equality in law that is perfect, “die-hard.”

Classical liberalism, as it accepts the state, accepts a first infringement of equality in law: officials and taxpayers, indeed, do not see themselves judged by the same rules of law (in the sense that the former are exceptionally empowered to live on coercion and to enjoy privileges such as, for example, the more extended right to strike, very advantageous pensions and health care mutuals, or guaranteed employment). However, classical liberalism does not only accept the state, it accepts the state within a national framework: it accepts the state as it covers the territory of a given nation, federated by a relative cultural and genetic homogeneity; in spite of notable exceptions, including that of Mises, classical liberalism does not promote the disappearance of national states in favor of a world state. As such, in addition of accepting the inequality in law between civil servants and taxpayers, classical liberalism accepts the inequality in law between domestic residents and foreigners. Anarcho-capitalism does not even want those two infringements of equality in law: the only inequalities that it considers legitimate are the inequalities of income and profession, any inequality in law becoming ipso facto guilty in his eyes – including the distinction between the official and the taxpayer, and that between the national citizen and the foreigner.

Concerning the relative cosmopolitanism that characterizes classical liberalism, and the adherence to a world government that makes the originality of Ludwig von Mises within classical liberalism, this passage from his treatise Liberalism is quite clear:

The metaphysical theory of the state declares – approaching, in this respect, the vanity and presumption of the absolute monarchs – that each individual state is sovereign, i.e., that it represents the last and highest court of appeals. But, for the liberal, the world does not end at the borders of the state. In his eyes, whatever significance national boundaries have is only incidental and subordinate. His political thinking encompasses the whole of mankind. The starting-point of his entire political philosophy is the conviction that the division of labor is international and not merely national. He realizes from the very first that it is not sufficient to establish peace within each country, that it is much more important that all nations live at peace with one another. The liberal therefore demands that the political organization of society be extended until it reaches its culmination in a world state that unites all nations on an equal basis. For this reason he sees the law of each nation as subordinate to international law, and that is why he demands supranational tribunals and administrative authorities to assure peace among nations in the same way that the judicial and executive organs of each country are charged with the maintenance of peace within its own territory.

Anarcho-capitalism condemns the distinction between the official and the taxpayer, as well as the distinction between the national citizen and the foreigner. Without being integrally cosmopolitan (and favorable to moral relativism or bio-cultural leveling), anarcho-capitalist cosmopolitanism is therefore a much more assertive, much more radical cosmopolitanism than is classical-liberal cosmopolitanism. In practice, one cannot but notice that there exists – in addition to those cosmopolitan tendencies that flow from a conceptual necessity – a very strong propensity of anarcho-capitalists to deny the existence of aggressive instincts, as well as that of races and cultures; and to condone, or even encourage, cultural leveling and miscegenation. This is accomplished on the grounds that only “individuals” would thus exist – i.e., individuals who are not only born tabula rasa and undifferentiated, but who have no other social link than the division of labor and trade. National genetic and cultural links are particularly denied. Such an approach deserves, in our opinion, the qualifier of “liberal Lysenkoism” [“libertarian Lysenkoism]; it is found among anarcho-capitalist, but also hybrid liberals: those who rally to the minimal state (or minarchy) of classical liberalism are nevertheless seduced – like anarcho-capitalists – by the ideal of racial and cultural leveling.

From the national-liberalism of 1789 to pseudo-nationalist anarcho-capitalism

One can conceive of “chemically pure,” radical liberalism as an egalitarianism which recognizes as legitimate only economic inequalities: income and occupation inequalities. Some anarcho-capitalists, however, claim to be defending the nation and developing a system that reconciles the preservation of nations with the universality of law: such is the case with Murray Rothbard, Hans-Hermann Hoppe, or Bertrand Lemennicier. We will see that these claims are invalid, and that such a version of anarcho-capitalism is only pseudo-nationalism. Nevertheless, there is indeed a liberalism that reconciles the ideal of the nation and the rejection of all forms of cosmopolitanism with equality before the law, or the universality of the law; and that liberalism is none other than that which inspired the Revolution of 1789 and the posterior European nationalisms.

We have seen that classical liberalism affirms the existence of nations and advocates that they cultivate pacifism and free trade, rejecting warmongering for the benefit not only of peace, but for an unlimited division of labor that extends beyond the frontiers; where men and capital circulate without the slightest restriction. The national-liberalism (or nationalist liberalism) of 1789, which served as the matrix for the various European nationalisms of the nineteenth century, differs from classical liberalism on the question of free trade and free immigration: it does not intend – unlike classical liberalism – to open borders to goods and people without discrimination. It is also distinguishable from classical liberalism on the question of pacifism: Napoleonic imperialism and the conflict of 1914-1918 constitute the purple epiphany of the warmongering inherent in bourgeois nationalism.

The national liberalism of 1789 combined the ideal of free enterprise with that of a perfectly unified nation, i.e., deprived of its intermediary bodies and of its rank inequalities. It intends to exacerbate the national sentiment so that the feeling of belonging to a nation henceforth arouses greater pride than that of belonging to some caste or class within that nation; it also attempts to erode the traditional status inequalities so that the nation will only know inequalities in terms of income and profession, and that individuals are reduced to mere cogs in the division of labor. Besides this, the national-liberalism of 1789 promotes a greater cultural homogenization: for example, in combating regional dialects and in imposing the use of a single “national language,” it can even promote the unification (into a single nation) of a geographical area that is composed of culturally and genetically related nations. Italy and Germany offer us two eminent examples of such unification.

On all those points, apart from forced unification and cultural homogenization, the national-liberalism of 1789 convergences perfectly with classical liberalism. Their model of the nation is rigorously the same: namely, that of a bourgeois nation. The disagreement comesover the questions of free trade, free immigration, and pacifism. As Vilfredo Pareto invites us to do, it is always worthwhile to distinguish between the “residue” and the “derivation,” the feelings that an ideology expresses and the supposedly logico-experimental varnish that covers them (often in disguising them). In fact, the national-liberalism of 1789, which claims to adhere to equality before the law, legitimizes a society that does not ignore inequality before the law, but only intermediate bodies (between the government and the individual); and where inequality before the law takes such a form that the dominant class, juridically and politically, becomes henceforth the bourgeoisie by virtue of the erasure of the intermediate inequalities in rank in favor of solely economic inequalities. The national-liberalism of 1789, like classical liberalism and even anarcho-capitalism, proposes to defend the bourgeois order and the commercial society under the guise of a mysticism of equality.

A version of anarcho-capitalism exists, which I have already referred to as pseudo-nationalist, which claims to be a liberalism that claims to preserve nations. Its adherents are, in truth, just as deluded on that question as those among the anarcho-capitalists who openly claim to reject the nation. The anarcho-capitalism à la Hoppe conceives, in more or less explicit terms, of the nation as an association based on property rights, and on the basis of property rights only. In other words, it envisions the nation as a vast ownership cooperative on which the state would be grafted ad hoc. The sympathies of those who adhere to the national-liberalism of 1789 for this variant of anarcho-capitalism stems from the condemnation of free immigration that has been formulated by the thinkers of Hoppe’s school. While they support free trade and the indiscriminate opening of national borders for the exchange of goods, they claim that the indiscriminate opening of those same borders to people violates property rights.

The inanity of such a conception of the nation cannot be overestimated. In the real world, national boundaries are not enshrined by property owners, but by governments. The nation is no more a fantasy exploited by governments to legitimize their authority over a given territory than it is an association of private owners. Once we get beyond the anarcho-capitalist chimeras, it is possible to apprehend the nation for what it is: a space federated by a given pecking order, and thus a certain juridico-political order; and by a territorial instinct which is expressed as much among the owners “at the bottom of the social ladder” as among those – bourgeois or aristocrats – who compose the ruling class and the state administration. It is also expressed in a relative genetic homogeneity, as well as that of culture: a common worldview, a certain canvas of memes. In fine, wanting to rebuild nations on the basis of property rights constitutes a modality of cosmopolitanism.

For an introduction to the theory of pecking orders, one may consult Howard Bloom’s interview with the Gatestone Institute:

Research on pecking orders – known technically as dominance hierarchies – has gone on now for roughly a hundred years. Schjelderup‑Ebbe, the naturalist who observed this “dominance hierarchy” in a Norwegian farmyard, called it the key to despotism. Schjelderup-Ebbe had discovered that in the world of chickens there is a social hierarchy, a division into aristocrats and commoners – a lower, middle and upper class. Pecking orders also exist among men, monkeys, lobsters, and lizards. And the struggle for position in a pecking order is not restricted to individuals. It also hits social groups.

Bloom’s interview is also interesting as an introduction to meme theory:

As genes are to the individual organism, so memes are to the social organism, or superorganism, pulling together millions of individuals into a collective creature of awesome size. Memes stretch their tendrils through the fabric of each human brain, driving us to coagulate in the cooperative masses of family, tribe and nation. . . . In law, politics, and economics, individualism is a personal credo of great importance. I, for one, am a passionate believer in free speech, democracy, and capitalism. But to scientists, the obsession to place emphasis on the individual has been a chimera leading them down a dead‑end path. History, either natural or human, has never been the sole province of the selfish individual, essentially preoccupied with preserving his genes. For history is the playfield of the superorganism – and of its recent step-child, the meme.

Concerning the argument that a free immigration policy is incompatible with respect for property rights, and therefore incompatible with anarcho-capitalism, that argument is merely a rhetorical trick, a “derivation,” than a logico-experimental form of reasoning. Indeed, it implicitly assumes that the nation constitutes a club or cooperative ownership, where the decision to authorize (or refuse) the entry of migrants is made by the owners (or by a gathering of members of the club). Yet that is a manifestly false conception of the nation (which is no more a club than it is a cooperative); and on the basis of such a premise, one could just as easily argue that free trade violates property rights, and therefore anarcho-capitalism, on the grounds that a policy opening up the nation’s frontiers to goods denies the right of the owners to decide which goods are allowed to cross the boundaries of their properties.

Free immigration and free trade must be limited, not in the name of anarcho-capitalism, but in the name of rejecting the cosmopolitanism inherent in classical liberalism and in all forms of anarcho-capitalism. Liberalism must be counterbalanced, limited by “civilizational” and geopolitical considerations: in this respect, it should be reminded that the invasion of Western nations by cosmopolitanism is only the culmination of a process of subversion which began with the abandonment of the warrior-based and sacerdotal culture, and with the advent of the commercial (or bourgeois) society. Classical liberalism has been involved in the march of cosmopolitanism from the beginning, in the sense that it has accompanied free trade and free immigration; for its part, the national-liberalism of 1789 has been involved in the march of the commercial society (without either classical liberalism nor anarcho-capitalism coming to intellectually oppose bourgeois society, or to defend the Indo-European tradition).