Leftists are fond of mocking conservative defenders of the Constitution, but they mysteriously morph into strict constructionists whenever anything threatens to overturn a law that suits their interests. Such is the case with the citizenship clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The same people who have advocated discarding the Second Amendment altogether are now rallying around the sacred infallibility of constitutional law regarding birthright citizenship.

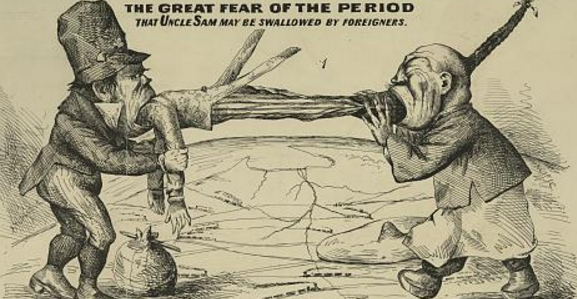

Indeed, cases like this point to the importance of taking historical context into account. The framers of the Constitution and the men who followed in their footsteps were highly intelligent, but few of them could have foreseen what America would become. They took it for granted that America was a white country and would remain so in the future.

The minutes of the 1866 congressional debate over the citizenship clause of the Fourteenth Amendment make for interesting reading. The clause is proposed by Senator Jacob Howard, who adds that “persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers” are excluded from it as dictated by the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”[1]

The phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” was added to ensure that the children of those with dual loyalties (such as diplomats) would not become citizens under the new amendment. Senator Lyman Trumbull states: “What do we mean by ‘subject to the jurisdiction of the United States?’ Not owing allegiance to anybody else. That is what it means.”[2] The concept of birthright citizenship is derived from English Common Law, under which a person owed allegiance to the ruler within whose kingdom he was born. Children born within a kingdom other than that to which their parents owed allegiance were excluded from this law and were not regarded as subjects of the ruler of that kingdom.

The Supreme Court stated in the Slaughterhouse Cases of 1873 that the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” excluded “children of ministers, consuls, and citizens or subjects of foreign states born within the United States.” This was dismissed as an obiter dictum in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), but it was the prevailing interpretation up to that point. This was again confirmed in Elk v. Wilkins (1884), in which the Court decided that an Indian who had severed his tribal ties was nonetheless not a citizen due to the fact that he owed allegiance to his tribe at the time of his birth.

Most of the debate itself revolves around whether Indians are subject to the jurisdiction of the United States. The senators disagree on whether Howard’s clause automatically disqualifies Indians by virtue of the fact that they belong to their own autonomous tribal nations, but they all agree that birthright citizenship should not apply to Indians.

Birthright citizenship, then, does not lawfully extend to American-born children of non-citizens and illegal aliens whose ultimate loyalty lies with another nation.

Still, it is noteworthy that this clause was powerless to prevent the gradual displacement of white Americans due to mass immigration. The semantic ambiguity of Howard’s clause and subsequent remark was easily exploited. Howard and the other senators probably did not think the issue was sufficiently grave as to warrant additional provisions.

There was one senator who was far-sighted enough to anticipate the potential long-term consequences of this. In the debate, a certain Senator Edgar Cowan of Pennsylvania urges Howard to articulate a more precise definition of who is a citizen of the United States and argues that non-whites should be explicitly excluded from the clause in order to guard against demographic invasion.

Another senator, John Conness of California, dismisses Cowan’s concerns and replies that there are not many non-white foreigners in the US and that they (mainly Chinese at the time) will eventually return to their country of origin. The issue is then settled. The senators continue to discuss the Indian question and do not address Cowan’s point. It is an instructive exchange and shows that the drafters of the amendment did not at all anticipate how history would unfold.

Here are excerpts from Cowan’s floor statement:

The honorable Senator from Michigan has given this subject, I have no doubt, a good deal of attention, and I am really desirous to have a legal definition of “citizenship of the United States.” What does it mean? What is its length and breadth? I would be glad if the honorable Senator in good earnest would favor us with some such definition. Is the child of the Chinese immigrant in California a citizen? Is the child of a Gypsy born in Pennsylvania a citizen? Have they any more rights than a sojourner in the United States? If a traveler comes here from Ethiopia, from Australia, or from Great Britain, he is entitled, to a certain extent, to the protection of the laws. You cannot murder him with impunity. It is murder to kill him, the same as it is to kill another man. You cannot commit an assault and battery on him, I apprehend. He has a right to the protection of the laws, but he is not a citizen in the ordinary acceptation of the word.

. . . Now, I should like to know, because really I have been puzzled for a long while and have been unable to determine exactly, either from conversation with those who ought to know, who have given this subject their attention, or from the decisions of the Supreme Court, the lines and boundaries which circumscribe that phrase, “citizen of the United States.” What is it?

So far as the courts as the courts and the administration of the laws are concerned, I have supposed that every human being within [the United States’] jurisdiction was in one sense of the word a citizen . . . . I have supposed, further, that it was essential to the existence of society itself, and particularly essential to the existence of a free State, that it should have the power not only declaring who should exercise political power within its boundaries, but that if it were overrun by another and a different race, it would have the right to absolutely expel them.[4]

He continues:

Is it proposed that the people of California are to remain quiescent while they are overrun by a flood of immigration of the Mongol race? . . . I should think not. . . . [I]f another people of a different race, of different religion, of different manners, of different traditions, different tastes and sympathies are to come there and have the free right to locate there and settle among them, and if they have an opportunity of pouring in such an immigration as in a short time will double or treble the population of California, I ask, are the people of California powerless to protect themselves? I do not know that the contingency will ever happen, but it may be well to consider it while we are on this point.

. . . [T]here are nations of people with whom theft is a virtue and falsehood a merit. There are people to whom polygamy is as natural as monogamy is with us. It is utterly impossible that these people can meet together and enjoy their several rights and privileges which they suppose to be natural in the same society; and it is necessary, a part of the nature of things, that society shall be more or less exclusive. It is utterly and totally impossible to mingle all the various families of men, from the lowest form of the Hottentot up to the highest Caucasian, in the same society.

It must be evident to every man entrusted with the power and duty of legislation, and qualified to exercise it in a wise and temperate manner, that these things cannot be; and in my judgment there should be some limitation, some definition to this term “citizen of the United States.”[5]

He observes that modern improvements in transportation have made immigration much easier and that, unless explicit provisions were to be made, the consequences of the amendment could be calamitous:

Distance is almost annihilated. They [the Chinese] may pour in their millions upon our Pacific coast in a very short time. Are the States to lose control over this immigration? Is the United States to determine that they are to be citizens? I wish to be understood that I consider those people to have rights just the same as we have, but not rights in connection with our Government. If I desire the exercise of my rights I ought to go to my own people, the people of my own blood and lineage, people of the same religion, people of the same beliefs and traditions, and not thrust myself in upon a society of other men entirely different in all those respects from myself. . . . Therefore I think, before we assert broadly that everybody who shall be born in the United States shall be taken to be a citizen of the United States, we ought to exclude others besides Indians not taxed . . . .[6]

Conness then responds to Cowan’s objections:

Now, I will say, for the benefit of my friend, that he may know something about the Chinese in future [sic], that this portion of our population, namely, the children of Mongolian parentage, born in California, is very small indeed, and never promises to be large, notwithstanding our near neighborhood to the Celestial land. The habits of those people, and their religion, appear to demand that they all return to their own country at some time or other, either alive or dead.[7]

He states with confidence that the Chinese population in America will never exceed forty-five thousand. He implicitly agrees with the premise that excessive immigration is not a good thing, but he asserts that white Californians are prepared to “provide against any evils that may flow” from the presence of the Chinese. He sees them merely as dutiful, unobtrusive laborers who will remain a tiny minority.

Of course, California’s Asian population ended up increasing exponentially; it now numbers five million. Its Hispanic population numbers about 15 million. Whites are no longer the majority in California, an omen of what America could look like in the near future.

Cowan’s argument is abandoned and not revisited. The vision of millions of non-whites flocking to American shores probably seemed so far-fetched that it was not worth discussing. The senators present did not think it was necessary to provide for such circumstances, so they moved on to more practical considerations.

No one in the debate actively disagrees with Cowan’s stance against mass immigration. Most senators at the time would have more or less agreed with his views. Had they entertained the possibility that Cowan’s dystopian scenario might come to pass, they would have gone to great lengths to prevent it from happening and would have made further qualifications to the Fourteenth Amendment. But the idea was laughable to most of them.

There is a salient parallel to the present day here. Many people see white nationalists as alarmist rabble-rousers. There are millions of white people on the planet, and, from a short-term perspective, it is easy to scoff at the idea that white people could eventually go extinct. In 1866, the notion that non-whites might immigrate here in droves was also an unthinkable prospect. Yet this was to become a reality with the signing of the Hart-Celler Act a century later.

This short exchange attests to the fact that the senators present—excepting Cowan—had little idea what they were getting into when they drafted the citizenship clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Regardless of Howard’s intended meaning, the question was not fully clarified or expanded upon by legislators because it was not perceived to be a major concern. They cannot be entirely blamed for their failure to address this, as they never would have anticipated that America would one day be swamped with immigrants and that there would be 4.5 million children born to illegal aliens in the US. It never occurred to them that whites might one day cease to be the majority.

Trump is right to put an end to birthright citizenship. It is what the men who created and amended the Constitution would support were they alive today, and it brings us one step closer to reclaiming America as a white country.

Notes

Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Session, p. 2890 (1866).

Ibid., p. 2893.

Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873).

Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Session, p. 2890 (1866).

Ibid., p. 2891.

Ibid., p. 2891.

Ibid., p. 2891.

No comments:

Post a Comment